Book Review: Progress and Poverty

by Lars A. Doucet, 2021

Part 0 - Book Review: Progress & Poverty 👈 (You are here)

Part I - Is Land Really a Big Deal?

Part II - Can Land Value Tax be Passed on to Tenants?

Part III - Can Unimproved Land Value be Accurately Assessed Separately from Buildings?

Listen

Introduction

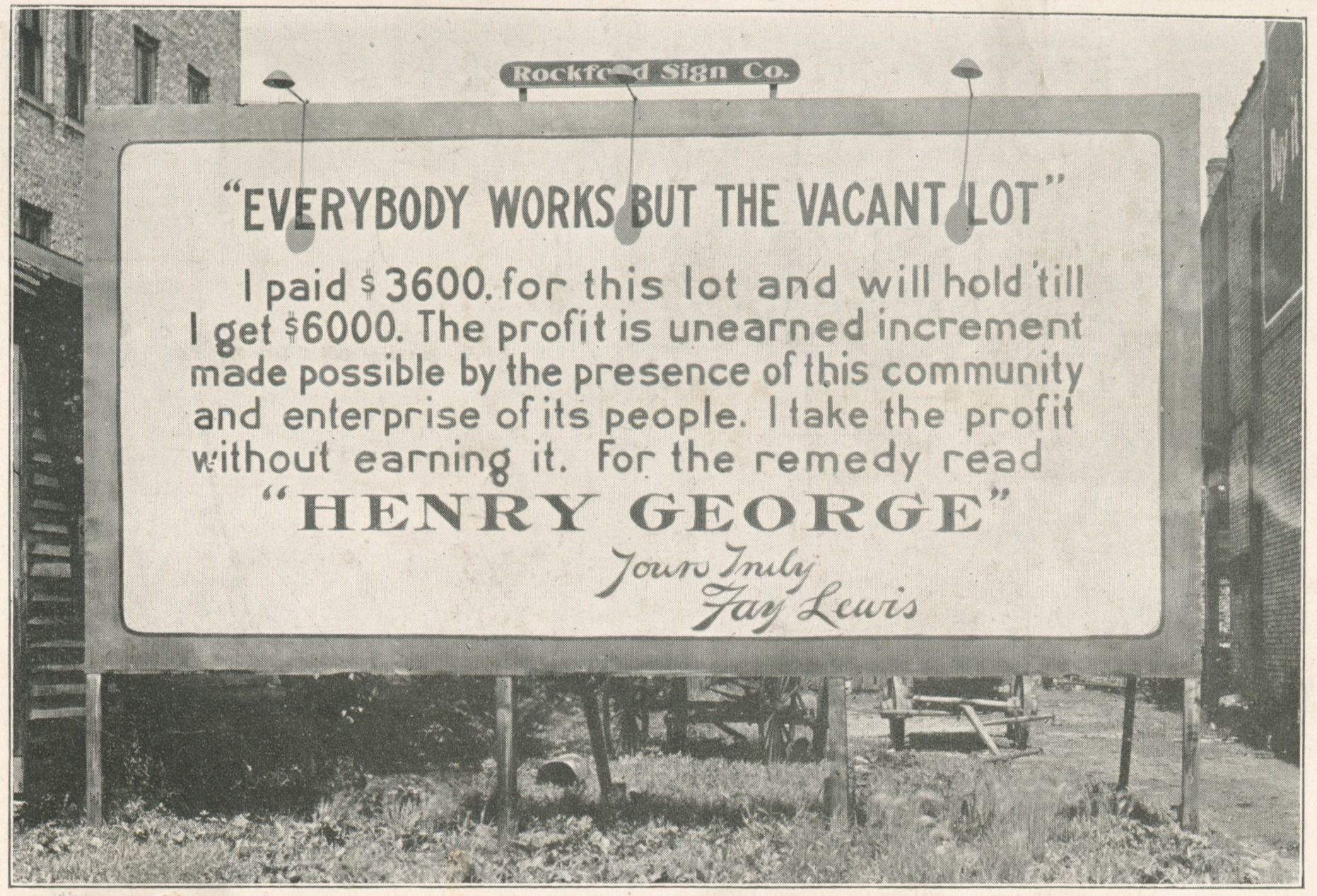

In 1879, a man asked "How come all this new economic development and industrialized technology hasn't eliminated poverty and oppression?" That man was Henry George, his answer came in the form of a book called Progress & Poverty, and this is a review of that book.

Henry George is variously known for leading an early movement that popularized Universal Basic Income, sporting a fancy beard while shouting "The Rent Is Too Damn High!" and inspiring a popular board game that was shamelessly ripped off and repackaged as Monopoly.

But he didn't just write a book. He also ran for Mayor of New York city in 1886, beating out some rando Republican named "Theodore Roosevelt," but ultimately losing to the favored candidate of Tammany Hall, who saw George's radical economic ideas as a threat to their well-oiled political machine (Andrew Yang take note). He ran again in 1897 but died just 4 days before the election, prompting a national outpouring of mourning. According to Ralph Gabriel's Course of American Democratic Thought, in New York alone 200,000 people came to see his body lying in repose, half of which had to be turned away. For context, that one crowd was roughly the size of 10% of the entire population of New York at the time.

I'm writing this book review for three reasons:

- George's arguments about land, labor, and capital present a fresh alternative to conventional ideas about "Capitalism" and "Socialism" (and whatever we mean by those on any given day)

- The book has timeless advice for navigating modern crises such as ever-rising rents, homelessness, and the NIMBY vs. YIMBY wars.

- This is a golden opportunity to shamelessly over-use the catchy phrase "By George!"

If I had to summarize the book in a single sentence I would put it this way:

Poverty and wealth disparity appear to be perversely linked with progress, The Rent is Too Damn High, and it's all because of land.

Table of Contents

The Book as a Book

Progress and Poverty is quite readable compared to other 19th-century economic tomes, but has a tendency to repeat itself. This isn't without purpose – George goes to great pains not to be misunderstood; rather than expecting his readers to tease out the meaning of dense prose and spending the next century arguing with each other about what he "really meant", he goes on for pages and pages beating a single concept to absolute death, just to be sure.

As a 19th century treatise of Political Economy, the book doesn't match what a modern reader might expect from a book on Economics because it's not packed to the gills with charts, graphs, tables, and statistics (though it does provide a good number of citations and figures). Nevertheless his argument was compelling enough to spawn an entire economic school of thought known variously as Georgism or Geoism that persists to this day.

Nowadays Georgism gets slapped with the "heterodox" label, but it's still relevant enough to get the likes of Paul Krugman and Milton Friedman to grudgingly agree to key points, and Friedrich Hayek is alleged to have been inspired by it to pursue economics in the first place. Marx, on the other hand, wasn't a fan, seeing it as a last-ditch attempt "to save capitalist domination and indeed to establish it afresh on an even wider basis than its present one... [George] also has the repulsive presumption and arrogance which is displayed by all panacea-mongers without exception." I guess you can't please everyone.

George spends the first few books of Volume I establishing terms and methodically tearing apart the prevailing economic theories of his day before presenting his own alternative theories about how the "three factors of production" – land, labor, and capital – relate to each other in the "laws of distribution." He then explains why the existing system causes poverty to advance alongside progress, and why we see industrial depressions. Then, he identifies the root cause of the problem (land ownership and speculative rent) and presents his solution (the Land Value Tax) in Volume II. He spends the entire second volume explaining why it is moral and just, how it should be applied, and why it will solve all of our problems.

For the sake of the reader's attention span, I'll just cover the chapters that constitute the core of George's philosophy. For sections I gloss over, I'll include a brief summary of the main point followed by a jump link to an appendix at the end of the article for those who want more detail. All block quotes are from Progress & Poverty unless otherwise marked.

Special thanks to my friend Adam Perry for helping me edit this piece, as well as to Nate Blair and blogger BlueRepublik (who have actual degrees in this sort of thing) for fact checking and answering my technical questions in the vain pursuit of not embarrassing myself.

Alright, let's dive in.

0. The Problem

George opens by observing an unkept promise made by Industrialists:

it was expected, that labor-saving inventions would lighten the toil and improve the condition of the laborer.

Industrialization should have freed humankind from drudgery and want. And yet George instead sees:

complaints of industrial depression; of labor condemned to involuntary idleness; of capital massed and wasting; of pecuniary distress among business men; of want and suffering and anxiety among the working class

If we finally have the necessary material conditions and technology for utopia, why this suffering, waste, and inefficiency?

And what's the deal with industrial depressions? How can there be periods where laborers desperately want to work but can't find employment at the very same time capital sits around in useless piles, begging to be put to productive use?

Contra popular explanations at the time, George argues it "can hardly be accounted for by local causes" such as military expenditures, tariffs, type of government, dense vs. sparse populations, or paper money vs. hard currency. This is because he sees the same basic problem everywhere no matter how different the countries themselves are. Behind all of these troubles George says there must lie a common cause.

Pulling no punches, the man lays the blame at the feet of progress itself:

that poverty and all its concomitants show themselves in communities just as they develop into the conditions toward which material progress tends - proves that the social difficulties existing wherever a certain stage of progress has been reached, do not arise from local circumstances, but are, in some way or another, engendered by progress itself

This is a pretty bold claim: namely, that the resilience of poverty, oppression, and inequality in the face of advancing economic development is not some embarrassing accident we'll eventually get around to fixing, it's an inescapable consequence of our socioeconomic system.

A Brief Interlude from the Future

It's been over 140 years since he wrote the book, so let's hop in my time machine and see how much of George's complaint is still relevant.

Back then, the United States was still in the throes of the Long Depression, which according to the shortest estimate lasted from 1873 to 1879.

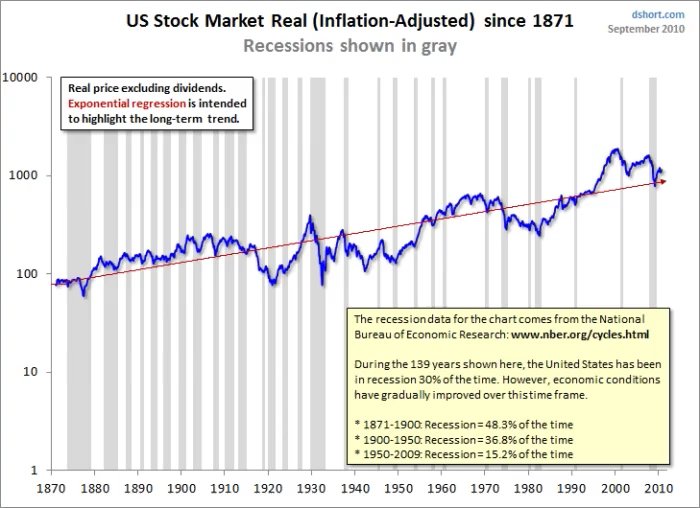

Below is a graph (source) of the boom-bust business cycle going back to the 1870's - clearly, recessions were much more frequent and severe in George's time than they are today. The late 1800's were wracked with so many panics and crises in quick succession that some historians count the Long Depression as lasting for a full 23 years from 1873 to 1896!

After the Great Depression in the 1930's, we see a sharp decrease in the duration and frequency of recessions. They're still with us now (and the one we're currently in is the worst since the Great Depression), but you'd still rather be living in 2021 than 1879.

So, have we solved the problem? Is George's complaint obsolete?

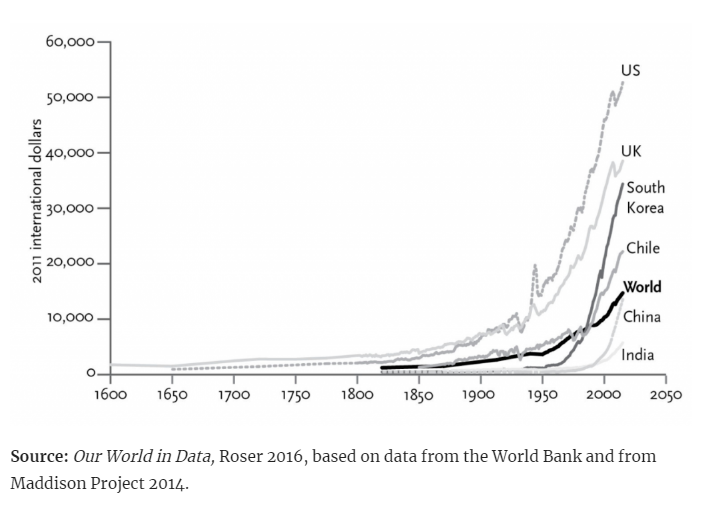

I mean, this graph of GDP per capita from Stephen Pinker's Enlightenment Now makes it look like in many ways things are getting better:

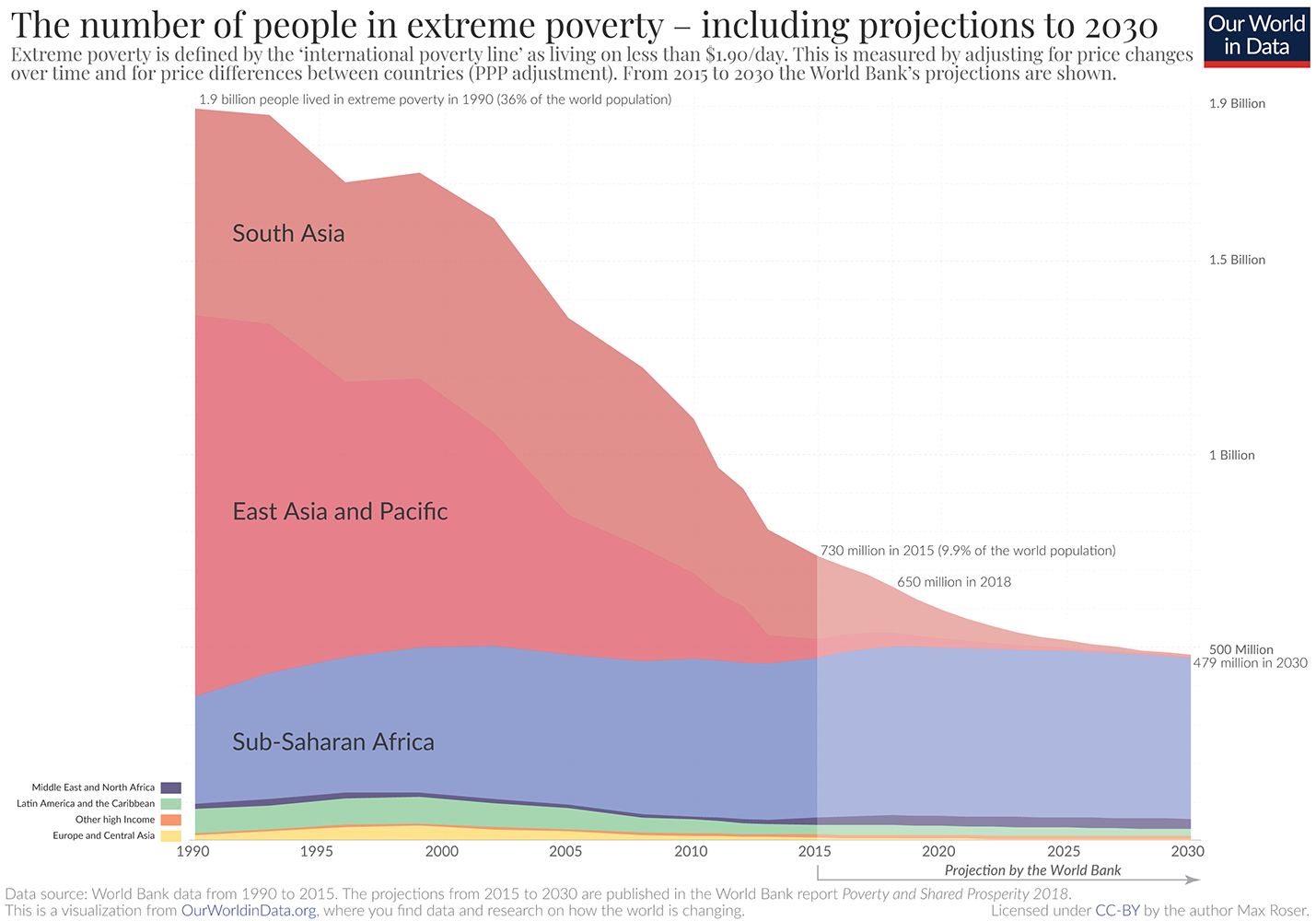

And heck, extreme poverty has been going down everywhere:

But this can't be the entire picture, or nobody would be complaining about poverty and inequality.

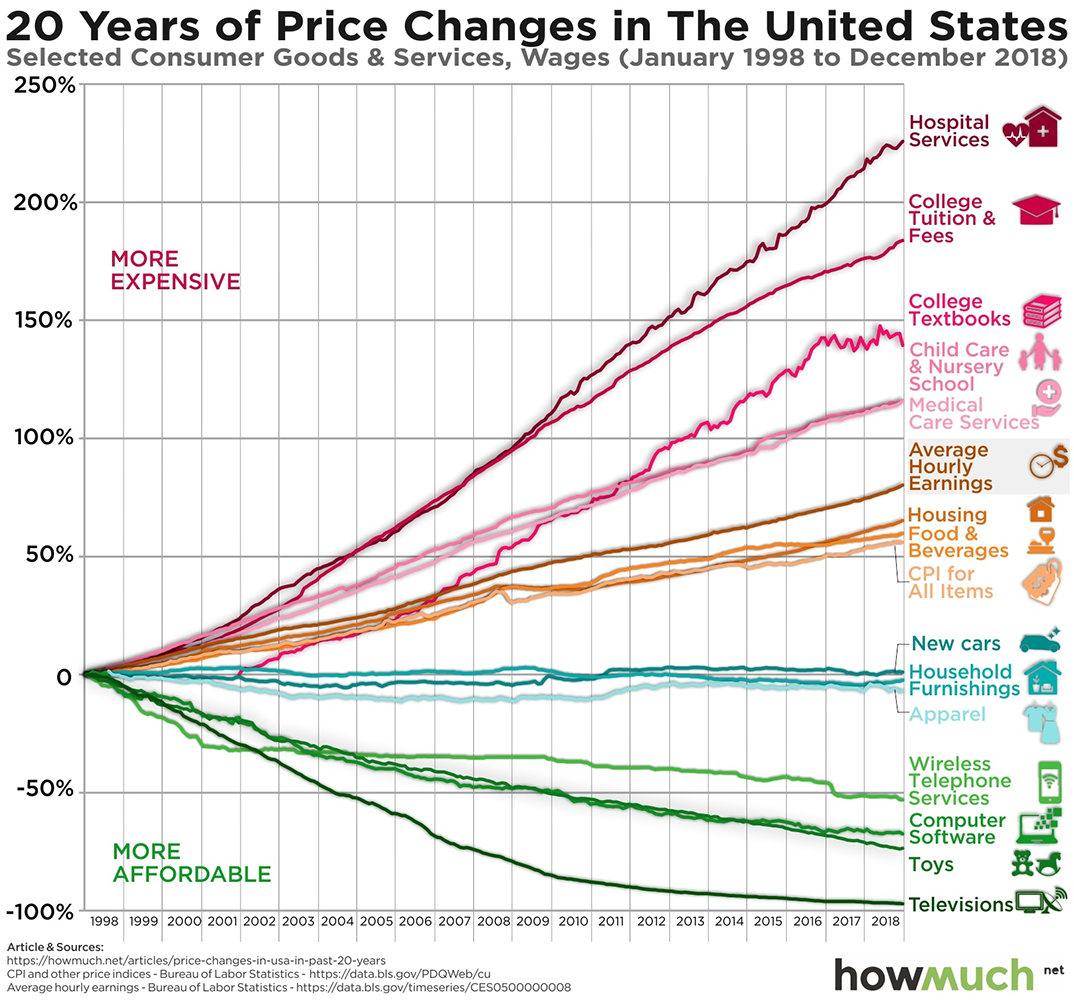

Here - this graph (source), shows that as consumer goods have gotten cheaper in the United States, health care, higher education, child care, etc., have skyrocketed in price, as examined in great detail in the article Considerations on Cost Disease.

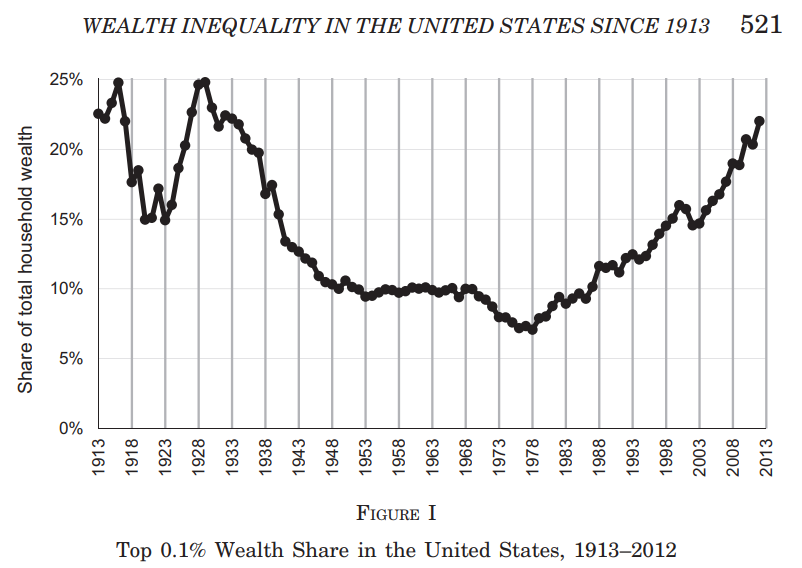

And what about Inequality? In the USA it seems to have reverted to levels not seen since the Great Depression, and even when it was at its lowest in 1978, the top 0.1% (not even the top 1%!) still enjoyed a massively disproportionate share of Wealth (source):

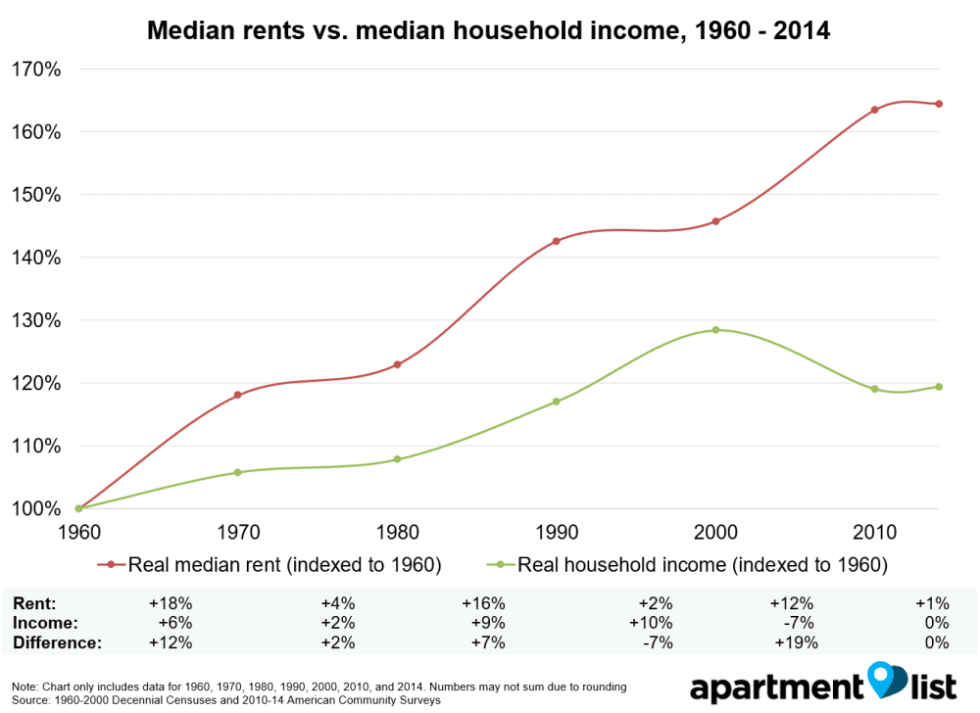

And of course, The Rent Is Too Damn High:

(source):

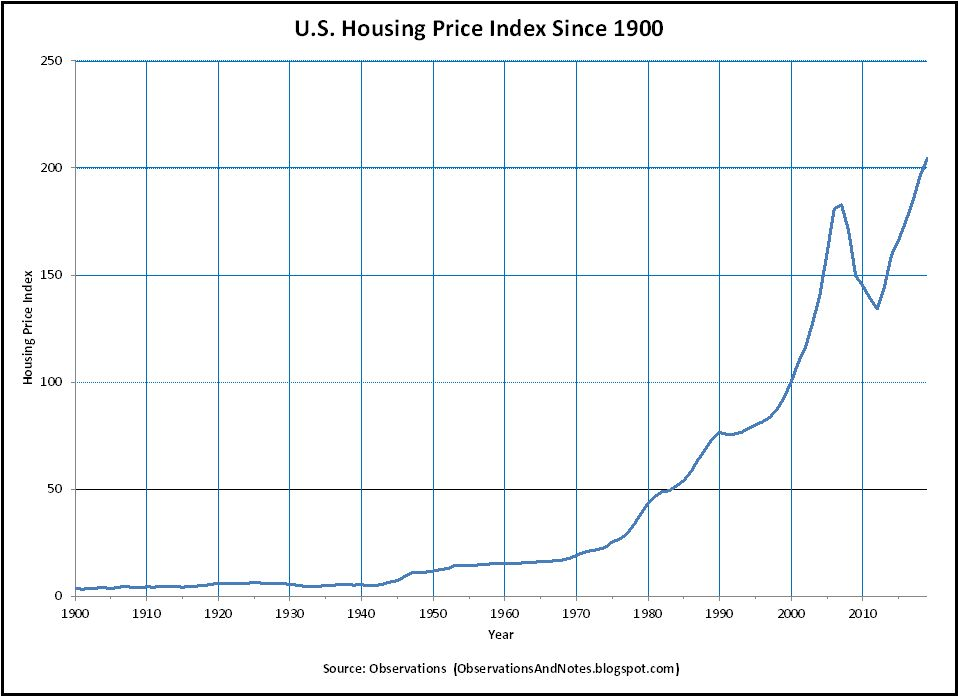

(source):

Although 2021 seems better than 1879 in absolute material terms, George's complaint still rings true: healthcare and higher education are increasingly unaffordable, inequality is as bad as it ever was, and The Rent Is Too Damn High.

And even if all of these measures had improved as well, we still have to contend with a fundamental complaint: how can human civilization have piled up an amount of wealth best described as absolutely banana pants insane, and yetstill have poverty, oppression and cyclical recessions? Yes, greed, evil, and human nature will always be with us, but isn't it weird that we haven't eliminated these economic problems the same way we've eliminated Smallpox, Scurvy, and having to write your scathing polemics about Thomas Jefferson by candlelight with a goose feather?

Giving the mic back to George, he closes the chapter with this haunting quote, first written 142 years ago:

If there is less deep poverty in San Fran Francisco than in New York, is it not because San Francisco is yet behind new York in all that both cities are striving for? When San Francisco reaches the point where New York now is, who can doubt that there will also be ragged and barefooted children on her streets?

I'll just leave this here:

Number of Homeless Children in U.S. At All-Time High; California Among Worst States.

I. Wages and Capital

George insists sloppy terminology leads to sloppy thinking. Naturally, he spends an entire chapter beating words to death to correct this.

The Meaning of the Terms

Let's start with Wealth.

The common usage, both then and now, is "anything with an exchange value." George doesn't like how this mixes dissimilar things.

By George, what is wealth?

Wealth is produced when Nature's bounty is touched by human labor resulting in a tangible product that is the object of human desire.

Labor is required, but the amount and type doesn't matter - George offers the example of simply picking a berry off a bush as an act that transforms nature's gifts into human wealth. Note particularly that human desire is an important requirement of wealth; it doesn't matter how much work someone put into something, if it doesn't gratify human needs or desires in some way, it's not wealth.

Speaking of human desire, let's talk about Value.

Where does a thing's value come from? The prevailing theory of the day was the Labor Theory of Value which originated with Adam Smith and David Ricardo, which says that Labor is the source of value. The early formulations were a bit ambiguous, here's Smith in Wealth of Nations for instance:

The value of any commodity ... is equal to the quantity of labor which it enables him to purchase or command. Labor, therefore, is the real measure of the exchangeable value of all commodities.

So... is a thing's value how much labor it takes to make the thing, or how much labor someone's willing to exchange for the thing?

Nowadays Labor Theory of Value is most commonly associated with Marx. Marx picks a lane and says the value of something is tied to the amount of "socially necessary labor" required to produce it.

George goes the other way:

It is never the amount of labor that has been exerted in bringing a thing into being that determines its value, but always the amount of labor that will be rendered in exchange for it.

- Henry George, The Science of Political Economy, p. 253

In other words, "a thing's value is whatever someone is willing to pay for it." This is in line with the so-called marginal revolution (the movement, not the blog) and modern theories of value.

Labor

Labor is the exertion of human beings. It's possible to labor to no avail (try punching a concrete wall), but typically humans labor towards an end, such as gaining wealth. But whether or not we accomplish anything with our efforts, George calls them labor. Labor isn't just making things, by the way – it's also moving or exchanging them.

Production

Production is labor applied "to the production of wealth." You know, productively. This is all human exertion that isn't punching a concrete wall and rewards you for your efforts with something that fits the definition of wealth. Said wealth is the "product of labor."

Wages

whatever is received as the result or reward of exertion is "wages."

No distinction here is made between blue-collar work and white-collar work – whether one is called "hourly pay" and the other is called "annual salary," George calls them both "wages." It doesn't matter whether you receive them from your boss, from customers, or from nature. If you do work and get something from it, you have received "wages."

With those basics under our belt, let's circle back to Wealth:

What are some examples of wealth?

By George, Gold is wealth. Teddy bears are wealth. Tesla roadsters and candy canes and young adult vampire romance novels are wealth. The same goes for fish you've caught, deer you've hunted, and cool looking rocks you've picked up on your morning walk. The value of these things may differ, but as long as they're tangible, originate in nature, someone ever did a lick of work to make or acquire them, and a human being somewhere desires them for any reason, they're wealth.

It gets a little clearer when we ask what isn't wealth.

And by George, Money isn't wealth.

Articles of gold are wealth because they're tangible things that have been dug up, crafted, and fulfill certain human desires. But paper currency, digital currencies, and other things that aren't inherently valuable but merely represent value are not wealth (outside of putting their physical articles in coin collections or making paper airplanes, and so forth). Now don't get the man wrong, these things are certainly valuable. They're just not wealth. They are certificates that represent claims on wealth. For any computer programmers in the audience, money is a pointer to wealth.

Likewise Stocks and Bonds and other financial instruments are not wealth. These are also just claims on wealth. A creditor's title to Debt isn't wealth, either, it's just a claim on the debtor's (typically future) wealth. And, writing as he was not long after the Civil War, George points out that Slaves are not wealth either but, represent "merely the power of one class to appropriate the earnings of another class."

Wealth, thus defined, is the terminal "ground truth" bits of the economy, and all the financial layers on top are fancy IOUs that just encode various claims on it.

George offers a thought experiment to test if something is wealth: if you produce a pile of gold, fish, or Lego bricks, you've clearly increased the amount of wealth in the world. But if you produce a giant pile of IOUs that just records who owns what and who owes what to whom, it doesn't matter how many of them you pile up or how long the chains of ownership get, you still haven't increased the amount of real wealth in the world.

Again, this isn't saying the IOUs aren't valuable, they are. But they're only valuable because they ultimately point to real wealth. If you magically transported everyone over to a hypothetical Earth 2, carrying over all of Earth 1's money and financial instruments but none of Earth 1's tangible wealth, the value of all those IOUs would instantly evaporate.

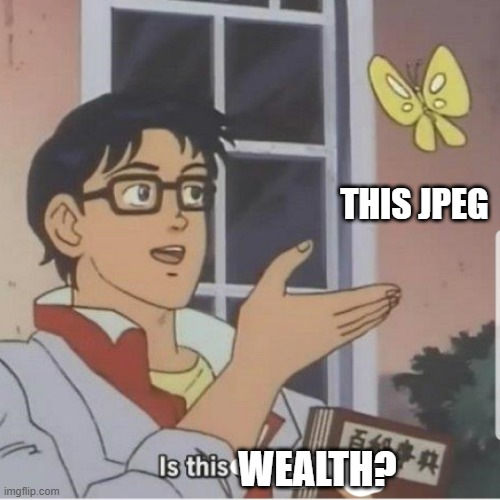

Now what about digital goods? Leaving things like Bitcoin aside for the moment, let's consider the case of a digital image file:

By George, this is wealth.

Digital though it may be, it's physically encoded on a storage device somewhere, and is thus tangible (it's not a pure abstract concept flitting about in Platonic heaven) and has its origins in nature. Human exertion built the computer that encodes it, and clicking the button that saves it to disk or displays it on your screen is labor. Finally, it directly satisfies human desires (mine, at the very least). It's value may be negligible, but it's wealth.

By contrast, the digital bit sitting in some database that says I own a particular eBook or mp3 is just a digital IOU – a claim on the wealth that are the physical bits on my local storage device or remote server that digitally encodes the files. The fact that digital files don't seem particularly physical, and that they can be trivially and endlessly copied, doesn't mean that Henry George, magically transported to today, wouldn't regard them as wealth.

Okay, so is there anything else that's not wealth?

By George, Bitcoin isn't wealth, in case you were wondering. It's just a (very fancy) financial instrument, a digital claim on wealth. And that goes for most crypto assets – a token on some blockchain that says I own a painting by Banksy is just another IOU, regardless of the technical sophistication of its distributed trustless ledger.

What about intellectual property? Copyrights, patents, and trademarks are all different forms of Monopoly – the exclusive, government-granted legal right to do a particular thing (publish a certain book, manufacture a certain product, use a certain name in business, etc). The exclusive right to do or produce a thing, valuable as it may be, is not the thing itself. By George, Monopoly is not wealth.

But there is something big that is wealth – the C-word.

Capital.

By George, Capital is "wealth devoted to procuring more wealth", and it's the next thing he insists everyone is hopelessly confused about.

He quotes Adam Smith, agreeing with him thus far:

That part of a man's stock which he expects to afford him revenue is called his capital.

...and also gives us a short etymology lesson on the origin of the term:

The word capital, as philologists trace it, comes down to us from a time when wealth was estimated in cattle, and a man's income depended upon the number of head he could keep for their increase.

("Per capita" being the Latin for "by head")

By George, all capital is wealth, but not all wealth is capital.

George notes capital is often described as being "stored up labor", and endorses this view – but what it really means, is capital is stored up production. It's not literally the labor that's stored up but the wealth generated by it, set aside and then dedicated to the purpose of getting more wealth.

George insists that it is the owner's intention that transforms wealth into capital. If you buy an old factory to throw parties in for your hipster friends, it's just wealth. But the minute you decide to put it to work to make something useful (or start charging your hipster friends a cover charge at the door), it becomes capital.

George therefore further insists that a laborer's daily bread and the clothes on their back do not count as capital, because a person has to eat and wear clothes whether they work or not. The laborer's tools (and arguably their steel-toed work boots) can however be counted as capital, because their purpose is to assist the laborer in getting more wealth by working for wages, and the laborer wouldn't acquire, use, and maintain those things otherwise.

George has more exclusions:

We must exclude from the category of capital everything that may be included either as land or labor.

Human exertion (labor) by itself can never be capital. The products of human labor become capital when they are stored up and set to the purpose of getting more wealth. To muddle this distinction defeats the point of having separate terms for those things at all, and prevents us from reasoning meaningfully about how they relate to one another. Labor is not capital, and neither is labor by itself wealth, it produces wealth – and if it ain't wealth, it ain't capital.

And that brings us to land.

Land, land, land.

By George, land is not wealth.

And it's definitely not capital.

The unique specialness of land is George's entire schtick and the very core of his philosophy.

The term land embraces, in short, all natural materials, forces, and opportunities

That means that a field or a meadow is "land", as is a mountain. But so are the fish in the sea, the clouds in the sky, veins of gold in the earth's crust, and the oil deep under ground. These things aren't yet wealth – not until human beings both a) desire them and b) touch them with labor.

So... land is not wealth.

But... how come? I mean, look: land is tangible, it "comes from nature", humans are always productively applying their labor to it, and it certainly seems capable of gratifying human desires.

George sees this reasoning as understandable, but insists it's the root mistake that leads other political economists astray – because for George, land just is nature itself.

Come again?

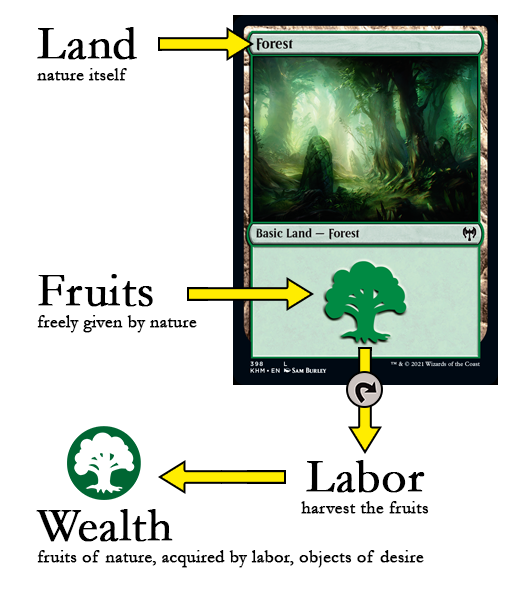

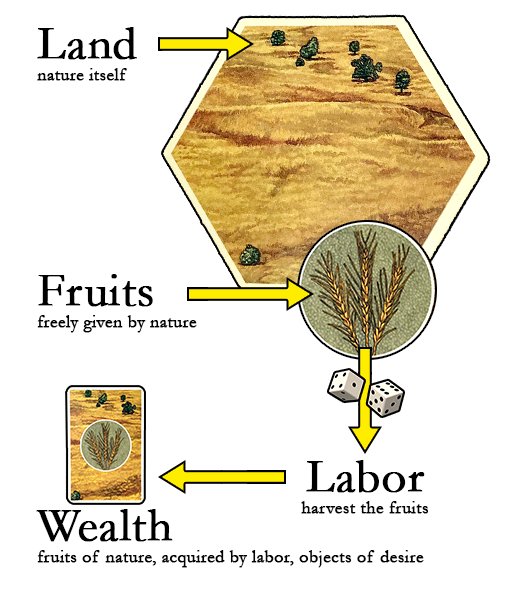

Land is the ultimate source of all wealth, but it's most useful to think of it as a generator, acompletely separate entity from the wealth that human labor and desire draws from it. Players of Magic: the Gathering and Settlers of Catan should already have a solid grasp of this distinction:

In modern times, George would grant electromagnetic spectrum and orbital real estate for satellites the same status of "land" that already applies to farmland and terrestrial real estate. We don't even need to speculate about whether he'd attach this status to sunlight because he straight-up predicted solar power:

Even the lack of rain which makes some parts of the globe useless to man, may, if invention ever succeeds in directly utilizing the power of the sun's rays, be found to be especially advantageous for certain parts of production.

(That's from Protection or Free Trade, footnote 19)

The important thing to grasp about land is that it comes before everything humans do or make, and is itself a thing no human can make.

Okay, smarty-pants, what about the Netherlands? They've been making land for centuries! Well, land in the Georgist sense doesn't refer simply to "dry land", but also the sea bed, the oceans, and the skies above. The "new land" in the Netherlands counts as an improvement to land that already existed. The seabed was always there, but by filling it in so you can walk around on it, now it's more useful to us (George has a lot to say about improvements to land, which we'll get to later).

Okay, what is land not?

nothing that is freely supplied by nature can be properly classed as capital

By George, land is not wealth.

And since it's not wealth, it's not capital.

Okay, we get it. Land is very special to Mr. George and we must never put it in the same category as wealth, labor, capital, wages, production, money, or anything else. Why exactly is this so damn important?

Well, by George, if you treat land the same way you would a bar of pig iron, an hour of work, or a dollar bill, before you know it you'll get poverty paradoxically advancing alongside progress, inexplicable bouts of industrial depression, literal genocides and holocausts (he's dead serious about this), and The Rent Being Too Damn High.

With terminology now firmly established, George moves on to the relationship between wages and capital.

3-for-1 special on Wages, Capital, and Labor

I'm condensing three chapters here because they all deal with the same basic thing.

The question George wants to answer is:

Why, in spite of increase in productive power, do wages tend to a minimum which will give but a bare living?

The conventional wisdom of George's time is that wages are governed by a fixed ratio between the number of laborers and the amount of capital devoted to their employment, because "the increase in the number of laborers tends naturally to follow and overtake any increase in capital."

So it doesn't matter how much capital you throw at employing workers, it'll just attract even more workers splitting it up, so although wages might temporarily wiggle a bit in the long term they'll always settle back to a "natural" minimum. (As we'll see in the next section, this argument stems from Malthusianism).

George spends some time methodically poking holes in the theory (it's predictions don't line up with the facts he observes), and then sets out to prove his replacement theory (emphases mine):

wages, instead of being drawn from capital, are in reality drawn from the product of the labor for which they are paid.

He pulls a G.K. Chesterton to make his point:

During the time [the laborer] is earning the wages he is advancing capital to his employer, but at no time, unless wages are paid before work is done, is the employer advancing capital to him.

He starts by identifying the source of confusion:

Because wages are generally paid in money, and in many of the operations of production are paid before the product is fully completed, or can be utilized, it is inferred that wages are drawn from pre-existing capital

I mean, the old theory seems sensible: the employer has capital and uses it to pay wages. But however you slice it, capital's investment gets paid back by production when it takes its cut, so does it even make a difference to talk about where wages are "drawn" from? Value goes out, value comes in, isn't it all a wash?

By George, it isn't: in the old theory, because capital "must come first", it follows that "industry is limited by capital - that capital must be accumulated before labor is employed", which leads to a reductio ad absurdum –

We are told that capital is stored-up or accumulated labor – "that part of wealth which is saved to assist future production." If we substitute for the word "capital" this definition of the word, the proposition carries its own refutation, for that labor cannot be employed until the results of labor are saved becomes too absurd for discussion.

George anticipates the following rejoinder – Well, when we say 'labor is paid out of capital' we don't mean it as an absolute statement for all stages of human development (or else we have a chicken-and-the-egg problem and civilization could never have begun), we just mean it applies to, say, every civilization that's left the stone age.

George will have none of it and spends three entire chapters relentlessly beating to death the idea that wages are drawn from capital instead of from production.

He starts with the simple case where wages are paid in the form of direct, concrete wealth, then moves on to the more complex case where people are paid in money and other instruments.

Laboring for wages:

Imagine a fishing village where nobody cooperates – each person digs their own bait and catches their own fish. Then they discover labor specialization and realize they can catch more fish together if one specializes in digging and the other in catching. So the digger digs, the catcher catches, and they share the fish. The digger really contributes as much to the catch as the one who physically pulls the fish off the hook even though the digger never directly "caught" a fish, and the fish he gets for his work is directly paid out of his contribution to the total production. Later, our fisherfolk invent canoes, and one stays home making and repairing canoes. This increases the haul of the digger and catcher, and the canoe-er gets paid out of her contribution to the increased production. And so it goes as society continues to advance. The work the specialist puts in causes more fish to be caught, and that person's wages is drawn from the growing pile of fish. As George puts it: "Earning is making."

George gives another example:

If I take a piece of leather and work it up into a pair of shoes, the shoes are my wages – the reward of my exertion. Surely they are not drawn from capital – either my capital or any one else's capital – but are brought into existence by the labor of which they become the wages; and in obtaining this pair of shoes as the wages of my labor, capital is not even momentarily lessened one iota... As my labor goes on, value is steadily added, until, when my labor results in the finished shoes, I have my capital plus the difference in value between the material and the shoes.

And another:

If I hire a man to gather eggs, to pick berries, or to make shoes, paying him from the eggs, the berries, or the shoes that his labor secures, there can be no question that the source of the wages is the labor for which they are paid.

George goes on to say it doesn't matter if you're paid in money or directly in wealth, because the money is a direct claim on the underlying wealth. It also doesn't matter if you get paid on commission. Imagine a whaling ship where each crewman gets paid a share out of whatever the ship catches. When the ship sails back into port with a hold full of whale oil and bone, the crew gets paid in money, the owner simultaneously adds to his capital oil and bone. The crew's money directly represents their share of the concrete wealth that is the oil and bone. The owner's capital hasn't decreased, and the workers drew their wages directly from the production.

So let's get to the point, Mr. George – wages aren't drawn from capital but instead from production. Great, let's grant that – so what?

George hammers away at this because thinking wages are drawn from capital leads to a false conclusion, namely that "labor cannot exert its productive power unless supplied by capital with maintenance."

"Maintenance?" Well, workers need food and clothing and they get paid by their employers, so you could imagine capital as a limiting factor on labor. But by George, food and clothing isn't capital, it's just wealth, as we said before.

And with regard to wages, the point is that the employer always gets "paid" first, because the second the laborer produces value, the employer's capital increases:

As in the exchange of labor for wages the employer always gets the capital created by the labor before he pays out capital in the wages, at what point is his capital lessened even temporarily?

Okay, but what if I'm just a terrible businessman and I pay somebody $500 an hour to smash Ming vases, then sell the fragments as aggregate to a construction crew for a few pennies a pound, all at a tremendous loss? Surely then the laborer's wages must be drawn from my capital, because there's not enough productive value generated by the labor to draw them from!

George says okay, sure, but only because I'm an idiot and will soon be out of business:

Yet, unless the new value created by the labor is less than the wages paid, which can be only an exceptional case, the capital which he had before in money he now has in goods – it has been changed in form, but not lessened.

Fair enough, Mr. George, but what if I'm building some enormously expensive multi-decade project, like a dam or a nuclear power plant or a cathedral? The kind of thing we call a "capital-intensive" project? What do you have to say to that?

George points out that as laborers labor, they progressively add value to whatever they're producing. Take the case of a shipwright building ships for an employer – even if the boss can't sell a half-finished ship, it still holds value (for one, it costs less to finish a half-finished ship then no ship at all). And with every stroke of the laborer's work, the employer who owns the shipyard gets an incremental increase in his stock of capital.

It is not the last blow, any more than the first blow, that creates the value of the finished product – the creation of value is continuous, it immediately results from the exertion of labor.

A pedant would point out that the "last hit" that finishes the product which makes it ready for market adds disproportionate value, but George's point is just to establish that value is continuously created, and doesn't magically come into being allat once right at the end.

George further points out that if you look at things like agriculture you'll see the market directly acknowledging his theory:

As a plowed field will bring more than an unplowed field, or a field that has been sown more than one merely plowed... It is tangible in the case of orchards and vineyards which, though not yet in bearing, bring prices proportionate to their age.

George freely admits that capital can be required for certain kinds of work, but he disagrees with what its purpose is. It's not a pool that wages get paid out of.

He goes on for another chapter on "The Maintenance of Laborers Not Drawn From Capital" but I think we can safely skip it and move on. TL:DR – George hammers to absolute death the idea that Laborers derive their own maintenance (food/shelter/clothing/etc) from their wages, with George insisting it is drawn from production and... you guessed it, not from capital.

At least some of George's ideas will not seem so radical to modern readers (especially those already critical of capitalism or neoclassical economics), but it's important to understand that at the time almost everything he was saying was considered deeply radical and shocking. Capital was the fundamental driving force of the economy and labor was utterly dependent on it, and the Malthusian theory of overpopulation was the accepted explanation for why wages were low and workers were starving.

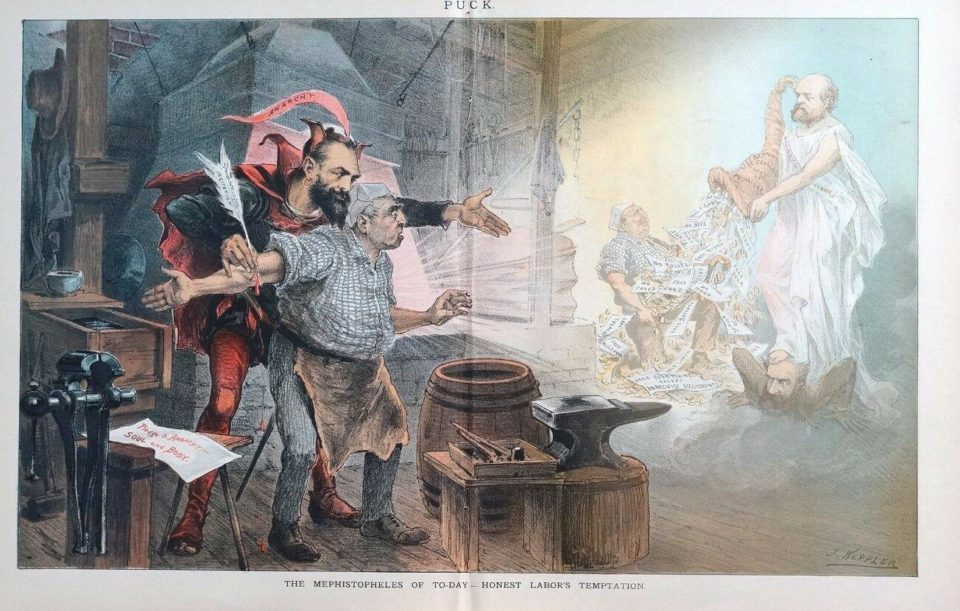

Political Cartoon literally demonizing Henry George – Puck magazine Oct. 20, 1886

The Real Functions of Capital

Okay, Mr. George. You've spent three whole chapters beating me over the head with what the functions of capital aren't. So what are the functions of capital?

Capital "increases the power of labor to produce wealth."

How?

- By enabling labor to apply itself more effectively (power tools go brrrr)

- By availing labor of the reproductive forces of nature (cows make baby cows)

- By making possible the division & specialization of labor (you dig bait, I'll catch fish)

Capital is a force multiplier that supercharges the productive power of labor. It doesn't supply labor with raw materials (nature does), nor does it provide for the maintenance of workers (who eat bread by the sweat of their own brow).

George says this is why capital isn't a limit on industry.

...okay, George grants that capital may limit the form of industry. You can't plow without a plow or milk without a cow. George also grants that the lack of specialized tools can greatly limit productivity because you don't get the benefit of the force-multiplying effect of capital.

Um... aren't you contradicting yourself here, Mr. George? You spent all this time hammering home your doctrine of wages to prove that capital doesn't limit industry, but you just said its absence can limit both the form and the productivity of labor!

Time to unpack what we mean by "limit" and be super clear about it from now on:

But to say that capital may limit the form of industry or the productiveness of industry is a very different thing from saying that capital limits industry.

Okay, what do you mean?

For the dictum of the current political economy that "capital limits industry," means not that capital limits the form of labor or the productiveness of labor, but that it limits the exertion of labor.

Okay, I think I see what he's saying. The existing school of thought says that because capital provides labor with both materials and maintenance, therefore if capital dries up, labor productivity must go down because workers will have nothing to work on, and nothing to eat or wear. Labor is thus "limited" by capital, for without it is literally and metaphorically starved for capital.

But George says no – the only way capital actually "limits" productivity in real life is in the degrees by which it force-multiplies labor's productivity and unlocks certain forms of labor in the tech tree. The kind of "limit" George objects to is the idea that you need capital just to get any work done at all, or that without capital to sustain it, labor will shrivel up. Instead, capital is rocket fuel that labor supplies to itself by investing a portion of its wages.

And yet, with all the awesome slots we've unlocked on the tech tree, and barrels and barrels of rocket fuel to fire up eager laborers, we still find our economy sinking into mysterious depressions. Something is gumming up the works, but it's not a simple scarcity of capital:

the real limitation is not the want of capital, but the want of its proper distribution

Or as G.K. Chesterton said, "Too much capitalism does not mean too many capitalists, but too few capitalists." This might seem like a pedantic distinction – misallocated capital could be said to be "scarce" capital – but they're not the same thing at all. As Francis Bacon said in 1625:

Riches were like [Manure]: When it lay, upon an heape, it gave but a stench, and ill odour; but when it was spread upon the ground, then it was cause of much fruit.

Because the prevailing theories of George's time are based on incorrect ideas about the relation between wages and capital, "all remedies, whether proposed by professors of political economy or workingmen, which look to the alleviation of poverty either by the increase of capital or the restriction of the number of laborers or the efficiency of their work, must be condemned."

In short, more investment, more protectionism, and more efficiency programs can't, won't, and haven't fixed poverty and industrial depressions because they all proceed from false premises.

Having finally beaten the nexus of wages, capital, and labor into a bloody pulp, George turns his eyes towards another leading theory for why everything is terrible: the specter of overpopulation.

II. Population and Subsistence

The entire second book might as well be titled "Why Malthus is Dumb and Wrong and Bad."

It's dedicated to dunking on Malthusianism, a philosophy that ascribes economic crises to the exponential growth of the human population, which must necessarily end in catastrophe.

according to Malthusian theory, poverty appears as increase in population necessitates the more minute division of subsistence.

George attacks Malthusian ideas not just because they're wrong, but because they make it easier to accept the prevailing theory of wages (as more capital is allocated, laborers will keep popping up like weeds to gobble it up, so wages must eternally stagnate). George draws a straight line between these faulty ideas and holocausts and genocides – specifically citing how colonial oppression in China, India, and Ireland were explicitly justified on Malthusian grounds. One million people died in the English-engineered Irish potato famine alone, and when you add in those who fled the entire population declined by 25% percent. And this isn't a tenuous link either – George directly connects the completely avoidable famine to his favorite bugbear, private landownership and extortionate rent.

Given that Malthusianism is now widely discredited I'm just going to skip this chapter, but if you want to hear George in all his righteous fury, check out Appendix A (there's a link that returns here at the end):

Appendix A: George Dunks on Malthusianism

III. The Laws of Distribution

When society produces wealth, who gets different shares of it, and why?

Let's start by beating some words to death.

By George, we're told that there are three factors in production: Land, Labor, and Capital. For each of these terms there must be a "law of distribution" that explains how each gets compensated for its part in production.

The reward you get from production by owning Land is called Rent.

The reward you get from production by supplying Labor is called Wages.

The reward you get from production by supplying Capital is called ... um, what?

We're looking for a term that clearly expresses the return to capital alone and nothing else.

The closest thing we have is Interest, and that's probably good enough.

George gives the common definition of interest as "the return for the use of capital, exclusive of any labor in its use or management, and exclusive of any risk, except such as may be involved in the security." This is pretty close to what we want – something that expresses the sole return to capital without mixing in anything else.

But ... what about Profits?

Profits is "almost synonymous" with revenue, assuming you have some left after you deduct expenses. It means a gain in money or wealth, but the trouble is this gain is a mix of rent, wages, and "compensations for the risk peculiar to the various uses of capital." What we want is a term that means the return to capital alone, totally separate from the return to laborers and landowners.

To talk about the distribution of wealth into rent, wages, and profits is like talking of the division of mankind into men, women, and human beings.

George spends a few pages talking about how everyone from Adam Smith on down got confused about this (spoiler: it's tied up with thinking wages are drawn from capital), before presenting his model for how it all works. If you want to see him knock that stuff down, see Appendix B (there's a link that returns here at the end):

Appendix B: George Dunks on the Conventional Laws of Distribution

Here's George's model for how it all works:

Land is"all natural opportunities or forces" and its return is rent

Labor is "all human exertion" and its return is wages

Capital is"all wealth used to produce more wealth" and its return is interest

George says the false assumption at the root of the old theories is in thinking of "capital as the prime factor in production, land as its instrument, and labor as its agent or tool."

George makes the following assertions:

- "Labor can be exerted only upon land"

- "It is from land that the matter which it transmutes into wealth must be drawn"

- "Capital is not a necessary factor in production"

Therefore, we should always put land first in all our inquiries rather than capital, which ought to come last.

George then sets out his three laws of distribution.

The Law of Rent

Let's be careful about the word "Rent." In modern usage, there is the concept of "Economic Rent" as well as "Rent" in the everyday sense of regular payments you make in exchange for the use of something that you are "renting." The modern definition of "Economic Rent", per Wikipedia is:

economic rent is any payment ... to an owner or factor of production in excess of the costs needed to bring that factor into production

To be clear, Economic Rent is a bad thing – all taking, no giving.

When George uses the word "Rent", he specifically means the return to land, and this is what he says it is:

Rent, in short, is the share in the wealth produced which the exclusive right to the use of natural capabilities gives to the owner.

Land has zero cost of production because it's already there and you can't make it. This means that any payment or benefit you can realize by excluding others from using land (or its fruits) is necessarily "in excess of the costs needed to bring that factor into production."

By George, all land rent is Economic Rent.

Furthermore, any piece of land has only one seller, and no producers. This further meets the definition of **Monopoly**– Greek for "one seller." This is why you hear Georgists talking about "Land Monopoly."

Land has value because people are willing to pay you for the privilege of using it.

The price of rent derives from the most marginal land available.

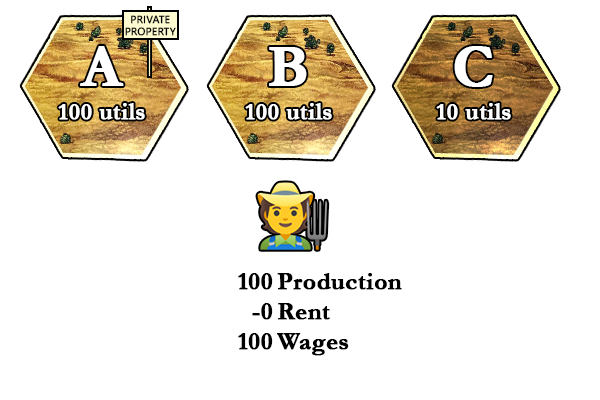

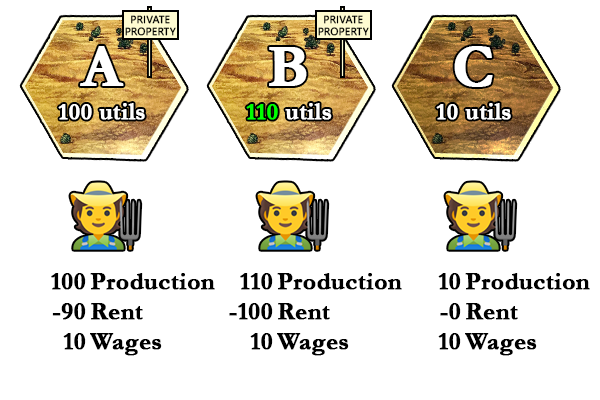

I'll explain with an example. Let's grade some imaginary lots according to their productivity by using abstract utility points, or "utils".

Lot A is good fertile land worth 100 utils.

Lot B is just as good, also worth 100 utils.

Lot C is crappy land worth 10 utils.

Let's say I own Lot A. I won't be able to charge you any rent to work on Lot A, if Lot B is freely available for anyone to use. Why would you pay even 1 util worth of rent if you could just work on Lot B, earn 100 utils, and keep it all?

But once I buy Lot B, now if you want access to 100-util Land you have to pay me. How much can I charge? Well, you could always work on Lot C for free, and it'll yield 10 utils. So the most I can charge is 90 utils (100 - 90 = 10).

So here's the Law of Rent – rent is determined by the "margin of production" (AKA the "margin of cultivation") – the difference between how much you can produce from a particular piece of land (Lot A or B) compared to the least productive alternative (Lot C).

Notice that I as the landlord am not really doing anything here other than owning the land, and yet I can extract a huge amount of value, because unlike capital, land is a hard limit on labor – you can't work without a place to work or without material that comes from nature. And so I take my share first without really contributing anything to production other than gatekeeping access to land.

Rent, in short, is the price of monopoly, arising from the reduction to individual ownership of natural elements which human exertion can neither produce nor increase.

C'mon, is land really such a big deal?

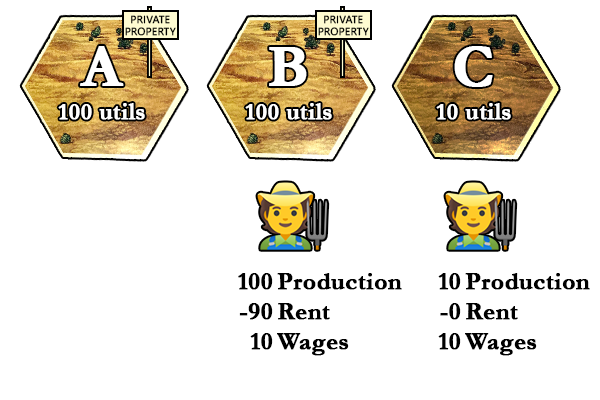

In the popular imagination we pit "capitalists" against "laborers" but a lot of those "capitalists" are landowners in disguise, because in non-Georgist frameworks land is typically considered a kind of capital. George says landowners oppress both labor and capital, cheating both hard work and investment out of their fair share.

Source: can't find the author of this image, closest I can get to its origin is this blog

Okay, but is this still relevant in the modern age, with the internet and work-from-home? Obsessing about land just feels so 19th century. Well, in Silicon Valley rents are famously off the charts, and those and all other rents seep into the economy at every level. Workers priced out of living close by have to spend more time and money commuting longer distances to work, and businesses must devote an increasingly larger share of their production to landowners who aren't actively contributing anything to productivity. What else could explain how a family of four making $100,000 in San Francisco is considered to be living below the poverty line?

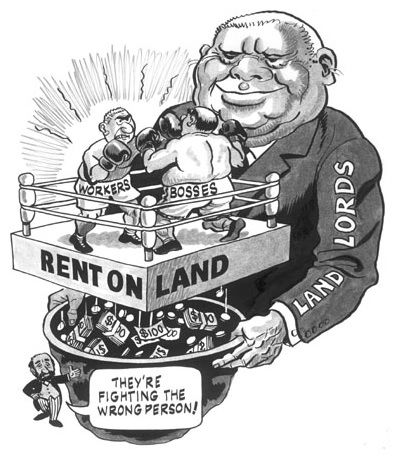

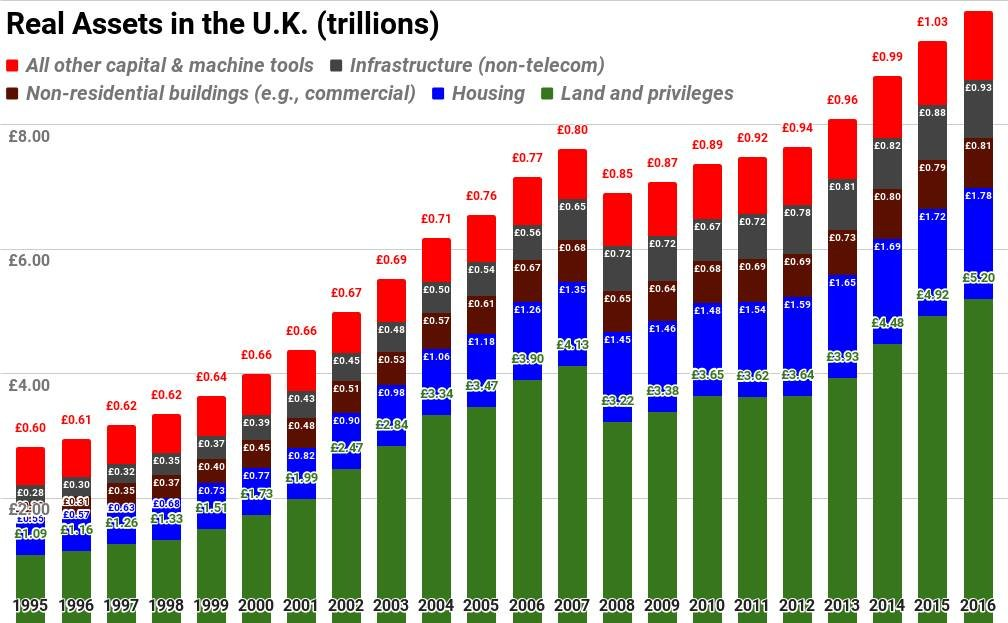

Here, take a look at this chart (source):

I found this in a tweet by Thomas Piketty, and it shows the breakdown of personal assets in Spain over the last 100+ years. The bulk of the value of personal assets is from landownership. This is still the case even though the chart includes "financial assets" – which are just IOUs that ultimately have something real (e.g. land or wealth) underpinning their value. If we exclude those, the true portion of overall value represented by land is even higher than this graph first implies.

And this isn't just Spain. Here's a graph Nate Blair made for the UK, excluding all financial instruments and only looking at real assets:

Based on data from the United Kingdom National Accounts: The Blue Book 2017. Published Oct 31, 2017. Revision Period: Beginning of each time series. Date of next release: July 2018. The "privileges" in "Land and privileges" are things like taxi medallions and patents, that were worth "almost zero" according to Nate.

No matter how hard you try, "there is no occupation in which labor and capital can engage which does not require the use of land." Whenever anyone does labor, the owner of some piece of land – whether it's the farm in the middle of Kansas that grows your food, the lot upon which the server farm sending you these bytes sits, or the ground that right now sits beneath your feet – is sticking their finger in the pie.

George reminds us that labor and capital will have to share whatever landowners take off the top of production in rent:

As Produce = Rent + Wages + Interest,

Therefore, Produce - Rent = Wages + Interest

So... what happens when the productivity of land goes up?

Let's go back to Lot A and Lot B, both 100-util fields. Let's say they belong to different landlords, and I'm a tenant on Lot B. I improve the soil of the field I'm working on so now it's worth 110 utils. What happens?

My landlord raises the rent, of course!

The only way wages (the return to labor) and interest (the return to capital) can go up as productivity increases, is if land values fail to rise at the same rate.

The Law of Interest

George wants to find the fundamental reason capital is able to produce wealth and justly claim a fair share of production.

Remember that capital is wealth devoted to getting more wealth. So if capital is wealth that begets wealth, it makes sense that if I lend it out to you, I miss out on the potential for it to grow while it's out of my hands. George says I am justly entitled to ask for more back than I originally gave you.

Let's say I loan you some corn seeds for a season. Had I not leant them to you, in a season's time I could have grown my own crop of corn and been left with more seed than I started with. So in a perfectly square deal, you need to give me back what I started with and what I could have expected to gain from natural increase (less the value of the labor required to get things started).

Likewise with any other article of capital – say bricks or lumber. In the time I've spent without it while it was in your possession, I could have found someone else who had a better use for it than I did and exchanged it for something of theirs that I had a better use for, leaving me with capital of greater value. George says the act of progressively exchanging things in a way that increases subjective value for all involved is analogous to the natural forces of nature that make living capital (like corn and cows) grow over time.

Remember, "subjective value" is real value. In a game of Settlers of Catan, if I have two bricks and you have two lumber, neither of us can build anything. The simple act of trading one brick for one lumber means both of us are better off because each of us can now build a road. The amount of bricks and lumber in the world didn't increase, but the amount of roads (or potential roads) did, and that represents a real increase in wealth.

Interest thus springs from the "reproductive" powers of capital, whether that's biological reproduction, or the more abstract reproductive force of exchanging things so that you have a more valuable distribution of capital than you started with.

As for how it relates to the other two returns to production – the more powerful the "power of increase" the capital has, the greater return interest can claim compared to wages. If you're ploughing a field and I lend you a tractor which makes you ten times as productive, I can justly claim more compensation for that than if I lend you a mule that only makes you twice as productive. However, rent still holds the whip hand, so the margin of cultivation determines how much return is left over to divvy up between interest and wages.

This is because the net "reproductive" value of capital goes down given rent is a general tax on overall productivity. The amount I would have gained by using the thing productively over the period of time it was out on loan (the amount I can justly charge in interest) is reduced by how much I have to pay in rent.

The Law of Wages

Wages, like interest, are limited by the margin of production. Within that limit there's not much to understand about how wages work except that people seek to satisfy their desires "with the least exertion," which is a fancy way of saying people don't like to get ripped off. If two bosses offer the same exact job, but one offers higher pay, I'm taking that gig. If two bosses pay the same, but one is asking for twice as much work, I'll tell that boss where he can stick it.

Wages depend upon the margin of production, or upon the produce which labor can obtain at the highest point of natural productiveness open to it without the payment of rent.

So with all three laws established George sums it up like so:

Where land is free and labor is unassisted by capital, the whole produce will go to labor as wages.

Where land is free and labor is assisted by capital, wages will consist of the whole produce, less that part necessary to induce the storing up of labor as capital.

Where land is subject to ownership and rent arises, wages will be fixed by what labor could secure from the highest natural opportunities open to it without the payment of rent.

Where natural opportunities are all monopolized, wages may be forced by the competition among laborers to the minimum at which laborers will consent to reproduce.

This is the reason George says that wages are so high in "new countries" where there's more land available than in countries where it's been locked up for centuries.

Here's how it all fits together:

Though neither wages nor interest anywhere increase as material progress goes on, yet the invariable accompaniment and mark of material progress is the increase of rent – the rise of land values.

And:

where the value of land is highest, civilization exhibits the greatest luxury side by side with the most piteous destitution

IV. Effect of Material Progress upon the Distribution of Wealth

As a society undergoes material progress, the rent goes up. Why?

Let's break it down. Three things contribute to material progress:

- Increasing population

- Technological advance

- Improvements in the social fabric

"Social fabric" is my term, George calls it "greater knowledge, education, government, police, manners, and morals, so far as they increase the power of producing wealth."

How does Population growth affect the distribution of wealth?

Generally speaking, as you get more people your productivity grows exponentially rather than linearly:

The labor of 100 men ... will produce much more than one hundred times as much as the labor of one man

That's thanks to specialization and division of labor. This happens without needing any technological advance. And as labor's productivity goes up, it makes it worth developing on more marginal (ie, less productive) lands, pushing the margin of production down (and outward geographically), which gives landlords more room to jack up rents.

A bustling town is a more valuable and productive place to live than a tiny hut in the middle of a remote forest. In the town there's a butcher, a baker, a candlestick maker, and others to supply you with whatever your heart desires. In the middle of the forest you have to do everything yourself, regardless of how abundant the natural resources might be. Every neighbor that moves in to town makes you "richer" in this sense because they contribute to the total productive potential of your community.

Population increase also drives productivity by making things valuable that were useless before. Let's say there's some resource on some land, say iron ore. Even if you have all the technology to mine and smelt it, you probably aren't capable of doing this whole operation yourself, and if nobody else lives there you don't have anybody to sell the iron to. It's the presence of a civilization that will give that ore its value, and for that you need to increase the population. Until population shows up to give it value, the ore is "latent potential" in the land.

By George, increasing population increases the share of rent (and decreases the share of interest and wages) in two ways:

- It lowers the margin of production

- It brings out the latent potential of land

How does Technological advance affect the distribution of wealth?

Tech saves labor. It lets you accomplish the same thing with less work, or more things with the same amount of work. This leads to more wealth being produced. Now, what do you need to produce more things? Capital is nice to have, but the two things you must have are labor, and land. So wanting to make more things means more demand for land, because you can't labor without it. And when you reach the productive limit of the land available to you, you seek out more marginal lands, extending the margin of production. Demand for land goes up, land values go up, and soon enough The Rent Is Too Damn High.

This means that as you introduce advanced machinery, the extra productivity they bring gets soaked up in rising land values, which gets extorted as rent.

every labor-saving invention, whether it be a steam plow, a telegraph, an improved process of smelting ores, a perfecting printing press, or a sewing machine, has a tendency to increase rent.

As a historical aside, I'll point out an extreme example of this: the cotton gin. This device massively decreased the amount of labor required to process cotton, which ironically increased the spread of slavery (slaves being laborers compelled to pay all their wages in rent). As the amount of slave labor required to process a unit of cotton went down, the margin of production was extended to more marginal lands. This caused the rents on the best lands to go up, further enriching slave-owning plantation landowners and increasing their influence. With the margin extended, demand shot up for land previously deemed unsuitable for cotton production, increasing the pressure to admit new states to the union as slave states.

The gin's effect on entrenching slavery was so profound that it's commonly blamed for prolonging the institution and laying the foundations for the Civil War.

How does improved "social fabric" affect the distribution of wealth?

Improvements to the social fabric that just make society generically better do the same thing. If the people in a neighborhood are nicer and more helpful, provide a robust network of mutual aid, start a bowling league and book club, etc, land values rise. That's because it's more desirable and productive to live in a place where you can e.g. trust your neighbor to watch your kid for an hour while also teaching them to whittle. Land value goes up, and so does the rent.

Now, let's talk about the expectations raised by material progress.

What happens when people know something will increase in value?

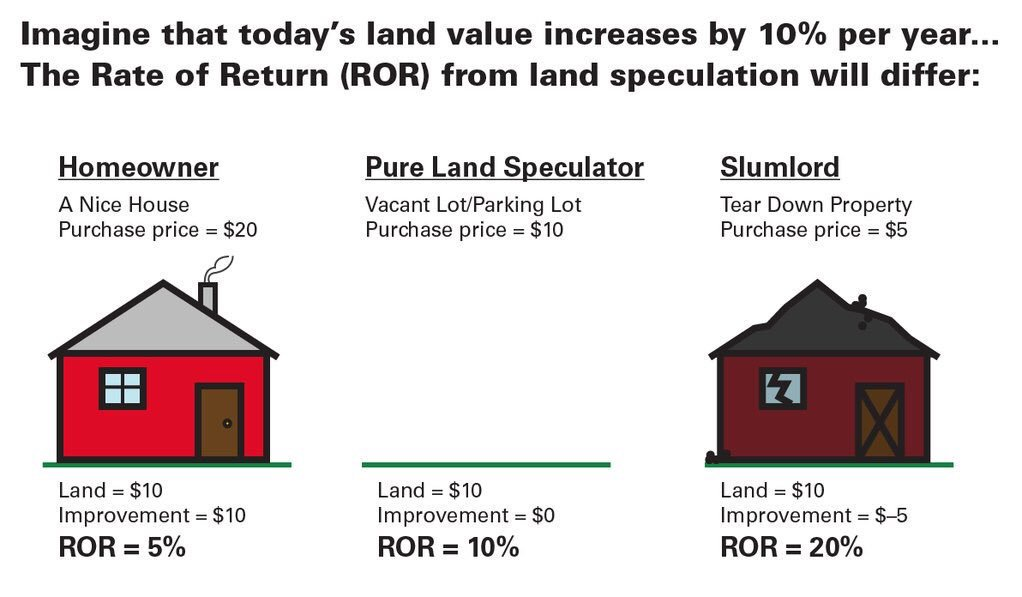

That's right, they buy it up in a speculative frenzy and hold on to it forever, further driving the price up. With conventional speculative instruments like beanie babies or tulips, the bubble eventually pops. But Land has unique properties that allow this vicious cycle to continue more or less indefinitely.

What happens when a city is growing, technology is advancing, improvements are being made to land, and so forth? Land values go up. Sure, speculators can still lose their shirts if a city falls into decline, but this isn't nearly as hard to predict as volatility in penny stocks or what next year's hot Christmas toy will be.

So as soon as there's a whiff of progress in a given area everyone starts HODLing land, but not to use it themselves. In fact speculators often keep it out of use, because this forces people to use less valuable land instead, pushing the margin of production down even further, forcing land values up, and now The Rent Is Too Damn High.

Georgist pundit geoliberal explains the mindset of a speculator:

The only thing investors actually maximize is risk adjusted rate of return. When you know rents will increase, your best return comes from buying extra land, not improving the land you have

Illustration courtesy of geoliberal

This is how it's possible to have urban blight and slums in areas with extremely high land values. Even if there's a temporary dip in prices, speculators know that if they just keep HODLing the general trend – absent a local collapse – is that land value always goes up.

Here's George:

Take now... some hard-headed business man, who has no theories, but knows how to make money. Say to him: "Here is a little village; in ten years it will be a great city—in ten years the railroad will have taken the place of the stage coach, the electric light of the candle; it will abound with all the machinery and improvements that so enormously multiply the effective power of labor. Will in ten years, interest be any higher?" He will tell you, "No!" "Will the wages of the common labor be any higher...?" He will tell you, "No the wages of common labor will not be any higher..." "What, then, will be higher?" "Rent, the value of land. Go, get yourself a piece of ground, and hold possession."

...without doing one stroke of work, without adding one iota of wealth to the community, in ten years you will be rich! In the new city you may have a luxurious mansion, but among its public buildings will be an almshouse.

I don't think it's a coincidence that real estate is one of the oldest investments on Earth and the principal concern of basically every war ever.

V. The Problem Solved

We had two questions at the beginning of this book: why are there industrial depressions, and why poverty seems to advance alongside progress.

You guess it, it's all because of land and rent.

By George, industrial depressions are caused by land speculation

Speculation has a tendency to press the margin of production down until it's just past its limit, forcing labor and capital to accept returns so small that it actually hinders production or ceases altogether.

The saving grace is that as long as the population is growing and/or technology is improving, productivity will go up, and production will start again. But soon enough the land values go up. This drives speculators bidding up the price of land, anticipating future even higher land values, which stresses the productive margin again.

So you get a cycle – productivity rises, economy booms, land values rise, production stagnates or stops. No matter how complicated or sophisticated the economy gets with layer upon layer of financialization and abstraction, when you unravel it all George says this is the ultimate cause.

Periods of industrial activity always culminate in a speculative advance of land values, followed by symptoms of checked production

This is how you get the baffling situation where able hands are eager and willing to work, capital is ready to employ them, natural materials are abundant, and yet the laborers are idle and the factories stand empty.

So that's it for industrial depressions. What about the other paradox of poverty advancing alongside progress?

By George, poverty advances alongside progress because of rent

The reason why, in spite of increase of productive power, wages constantly tend to a minimum which will give but a bare living, is that, with increase in productive power, rent tends to even greater increase, thus producing a constant tendency to the forcing down of wages.

George backs this up with several pages of specific regional figures demonstrating how land values have continued to explode all over the world.

By George, on average and in the long run, no amount of hard work from labor, no force multiplication from capital, no increased gain from co-operation and specialization, no labor-saving invention or increase in personal efficiency, work ethic, or morals, can escape the long reach of rent.

In short, increased power of production has everywhere added to the value of land; nowhere has it added to the value of labor;

George notes that the mass die-off of the Black Death in England in the 1300's significantly reduced the productivity of the individual laborer, and yet wages went up. That's because the decreased population also caused a massive drop in competition for land, in turn causing rents to plummet. (For more detail on this read about the Peasants' revolt, also known as Wat Tyler's rebellion).

George says the opposite happened during the reign of Henry VIII, who seized the lands of the church and those held in common by the peasants, and handed them out to newly minted aristocrats, which was followed by suppressed wages.

In the reign of Henry VII., half a bushel of wheat would purchase but little more than a day's common labor, but in the latter part of the reign of Elizabeth, half a bushel of wheat would purchase three day's common labor.

He sums it all up like this:

Material progress cannot rid us of our dependence upon land; it can but add to the power of producing wealth from land; and hence, when land is monopolized, it might go on to infinity without increasing wages or improving the conditions of those who have but their labor.

So there's our answer: the monkey wrench that causes the boom-bust cycle of industrial depressions is rent, and even though we have more than enough material wealth to provide for everybody's needs, rent prevents us from distributing it fairly and equitably.

Volume II

Okay, The Rent Is Too Damn High, and now we finally know why. What are we going to do about it?

Insufficiencies of Remedies Currently Advocated

George goes down the list of everything we've already tried and why it hasn't worked (or has worked, but less well than we hoped), which you can read about in Appendix C (there's a link that returns here at the end):

Appendix C: The Insufficiency of Remedies Currently Advocated

The Remedy

George says the solution is to make land common property.

He doesn't want to confiscate land, or force everyone to live on some giant hippie commune. He proposes instead to let everyone continue to "own" land exactly as they do now, but we should impose a special tax to neutralize the perverse incentives of land rent.

He anticipates a lot of pushback on this, and promises that his remedy:

- Is just

- Can actually be practically applied

- Will solve all our problems once and for all

Why the Remedy is Just

George asks, "what constitutes the rightful basis of property?" What gives you the right to say "this is mine?"

George asserts as self-evident the principle that a person is entitled to the fruits of their labor. What you make on your own time with your own resources, is yours to do with as you please – use it, give it away, trade it, destroy it. You don't harm anyone else doing so.

It follows that neither I nor anyone else am entitled to the product of your labor. If we're both independent hunter-gatherers, and you pick some berries from a bush, I don't have any fundamental right to demand them from you.

If you improve land in some way, you're entitled to own and use that, of course. That's the product of your labor. But to claim exclusive and permanent ownership of the land itself – from which all wealth springs and without which labor is impossible – is to demand the product of other's labor. So to invoke the sanctity of private property to defend private land ownership is self-refuting.

But what about the right of "I was here first?" Well, George points out that in most cases someone was there before you were, too (and often they were removed by force). Just because you arrived one second, one minute, one year, or one decade before someone else doesn't give you some fundamental right to exclude others from access to nature's free gifts. (Note: this doesn't give people the right to just come in your house and rifle through your underwear drawer at any time of day, we'll get to that).

And what about native populations? Isn't this just an excuse for colonialists to come in and steal their land by denying their claim of being on the land first? By George, no – this is a good time to point out that many Native Americans already had a roughly Georgist understanding of land – treating it as common property, and it was precisely the colonialists' conception of land as private property that was the mechanism by which the indigenous population was expelled and their lands seized.

The English first practiced this on their own people – once upon a time wide swaths of land in England were held in common until the government privatized those lands and gave them out to well-connected gentry in a process called Enclosure. If you've ever heard of the Luddites, you should know they weren't merely rebelling against the march of technology, they were also fighting against the forcible seizure of their lands by industrialists, who far from being salt-of-the-earth free-enterprise entrepreneurs, were in actual fact crony capitalists stealing the people's land with the aid of anti-free-market subsidies and armed thugs, all supported by Big Government™.

As a practical matter though, if you want to impose a Georgist policy, that only applies to territory your state has authority over. Indian reservations in the United States are supposed to be sovereign enclaves with their own jurisdiction. Native Americans should decide for themselves whether they want to adopt any particular policy.

The other reason the remedy is just, is that private ownership of land leads to serfdom.

The essence of slavery is that it takes from the laborer all he produces save enough to support an animal existence, and to this minimum the wages of free labor, under existing conditions, unmistakably tend.

George points out that even though Slavery was abolished, the Southern landowners just changed the brand name to "sharecropping" and were able to continue to extract tremendous wealth from "free" Black Americans in the form of rent.

Okay, but excluding evil Southern plantation owners, don't landlords deserve compensation for their work? What about Ms. Nguyen, the nice lady who manages your apartment block and went the extra mile for you when your A/C went out last summer?

I like Ms. Nguyen too, but let's contrast her with Mr. Slumlord, who owns the apartment block next door that's superficially identical, but who won't help you when your A/C goes out in the middle of summer.

Ms. Nguyen charges higher "rent" for her much better maintained units because part of that "rent" is actually her justly compensated wages for her labor in managing them, as well as interest from returns on the capital she's invested in their ongoing improvement and maintenance. She also collects a good bit of true Georgian rent because she is, after all, a landlord.

Mr. Slumlord puts in as little work as he can get away with and invests as little capital into maintenance as will keep the state off his back. His return is almost entirely rent. And the only reason he can charge rent in the first place is because of the valuable location – value the community produced, not him.

And that's the real injustice of land rent – the community produces the value, but the landlord charges rent to access it.

Practical Application of the Remedy

Okay, land as common property, rent must die, I'm sold. How do we actually do it?

George proposes a land value tax, or LVT.

Note I didn't say property tax. Property tax is a tax on the value of a piece of land and it's improvements. So if you're a homeowner, when you pay property tax, you pay tax for both the value of your house and the lot it's sitting on.

With land value tax you only pay tax on the "ground rent", which is the value of your land, but not the improvements.

What's an improvement?

By George, a little green house is an improvement. A fancy red hotel is an improvement. A garage, a sidewalk, a public park, a Starbucks, a hotdog stand, are all improvements. Installing a bunch of dikes in the Netherlands and dumping landfill into the seabed to turn wet land into dry is an improvement. All improvements come from labor, and optionally capital, and so its fair for those factors to take their return. If I "rent" you my hotdog stand (but not the lot it sits on) my return would be classified as interest in George's framework because the hotdog stand isn't land, it's capital – the stored-up fruits of my labor that I'm using to get more wealth.

(Modified from source, CC BY 2.0, author: Philip Taylor)

The problem with our current system is that when anyone in the community builds improvements, it makes adjoining land more valuable, and then those adjoining landlords jack up the rent. This makes things worse for everybody but the landlords. George's insight is that extra value from my improvement "spills over" from my land and is soaked up by the ground rent of your land.

So under a land value tax, we can correct for the perverse economic incentives, distortions, and oppressions that come from land rent, without having to actually take your land from you.

We may safely leave them the shell, if we take the kernel. It is not necessary to confiscate land — only to confiscate rent.

You also are 100% the owner of the improvements on your land, which won't be taxed. This is why Georgism doesn't mean people have the right to barge into your house in the middle of the night even though land is "held in common." Your house is still private property, but the value of the land it sits on is common property.

What if I plant some nice trees, and invest in some landscaping to stop erosion? Where's the line between "improvements" and "ground rent?" In most cases it's pretty straightforward to separately assess the value of a plot from the value of what sits on it (modern property tax assessors do this already), but George grants that in some edge cases with the passage of time at least some improvements will be subsumed into the land value and that's okay:

But it will be said: There are improvements which in time become indistinguishable from the land itself! Very well; then the title to the improvements become blended with the title to the land; the individual right is lost in the common right. It is the greater that swallows up the less, not the less that swallows up the greater.

Okay, ground rent bad. How much should we tax it?

By George, One Hundred Percent.

Take the rent the tenant has to pay each month, calculate the portion attributable to the value of the unimproved land itself, and send it to the taxing agency.

Effects of the Remedy

Wow! 100% tax rate on ground rent! Can we really do that? In practice Georgists often talk about rates closer to 85+% given real-world limitations in assessment, but the point is to hit it as hard as you possibly can. Get close enough and you still have good effects.

Won't land taxes jack up land prices? No, actually - in fact it will do the opposite, because such a tax is laser-calibrated to eliminate speculation, which makes up the bulk of inflated land values, and thus rent. Tax land for the full ground rent and you make real estate more affordable, not less_._

Won't it enable an all-powerful centralized nanny state? Quite the opposite – land value assessment is a fundamentally bottom-up, localized task, so it naturally empowers local municipalities at the expense of distant central authorities. Also, income taxes, wealth taxes, investment taxes, etc, require an ever-vigilant centralized bureaucracy peeking into every aspect of an individual's life to catch tax evaders, who have every incentive to hide their assets or even just flee.

Perversely, the IRS currently audits the poor at the same rate as the top 1%, even though higher earners are responsible for withholding the vast majority of tax money in fraud.

Land can't move or hide, and nowadays we have tools like GIS to make it even easier to assess. Under land value tax, nobody needs to pry into your personal life or impose burdensome accounting rules on your small business that actually entrench the power of giant corporations (who have entire departments devoted to serving up the Double Irish with a Dutch Sandwich).

A Brief Interlude From the Future

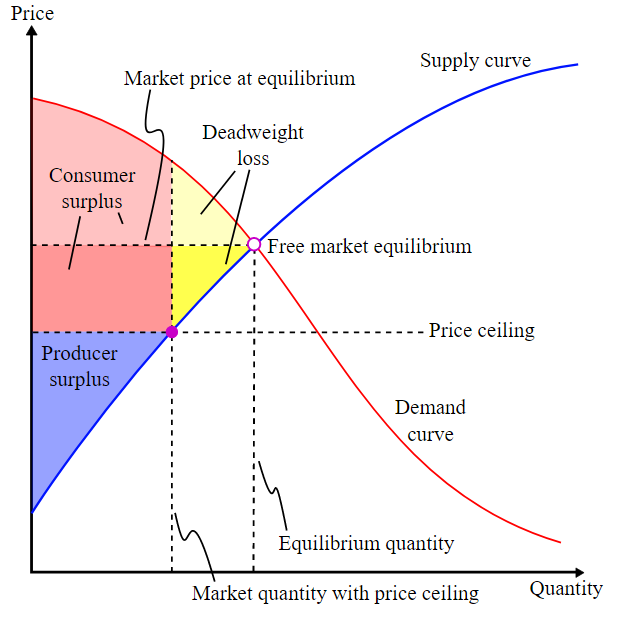

Today land value tax is widely considered to be the only tax that doesn't suffer from Deadweight Loss.

Deadweight Loss is the lost economic activity or value caused by some policy. It's often summarized by the phrase "If you want less of something, tax it."

Look at this chart, for example:

(source, CC BY-SA 2.5, author: SilverStar)

The place where the demand curve (red) and supply curve (blue) meet is the equilibrium point that the market naturally tends towards. But if we impose a price control lower than what the market will bear, the yellow area of the curve shows economic activity that can't happen. If you put price controls on gasoline, for instance, you'll get shortages because there's more demand than supply, and supply can't profitably rise to meet the extra bit of demand that's willing to pay a little more.

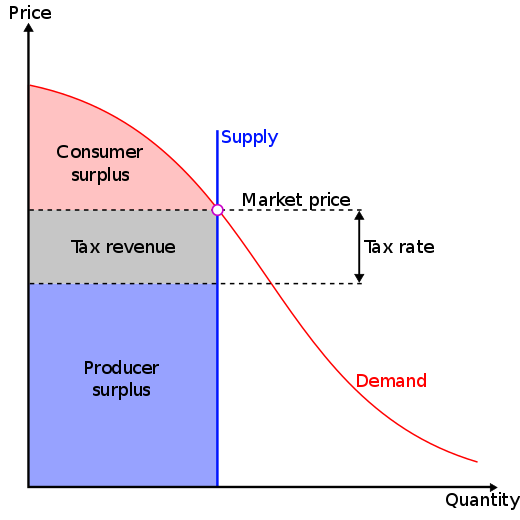

But here's how things look with a land value tax, notice that the supply curve is vertical – that's weird, what does that mean?

(source, CC BY-SA 3.0, author: Explodicle)

A vertical supply curve means no matter what the price of land is, the same amount will always be supplied. This is because you can't make land – the supply is effectively fixed. Remember, the Netherlands doesn't count because the sea bed is land, and filling it in is just an improvement to land that already existed. And even if we granted "The Netherlands occasionally makes land" for the sake of argument, the amount of land "created" in this way is pretty darn negligible in the grand scheme of the economy, and almost exclusively the domain of governments or state-owned actors.

The supply of land being fixed has some really interesting properties. By contrast, consider oil, the supply of which is not fixed. If we tax oil, some of the more marginal wells will be too expensive to operate and make a profit, so producers shut those down and the supply of oil decreases. Deadweight loss comes from a producer's ability to change the amount of product they supply in response to price signals. You'll notice the above graph of land tax has no deadweight loss at all!